Image: Mel Groves

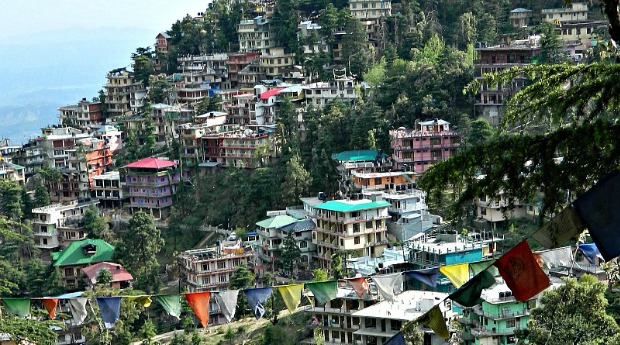

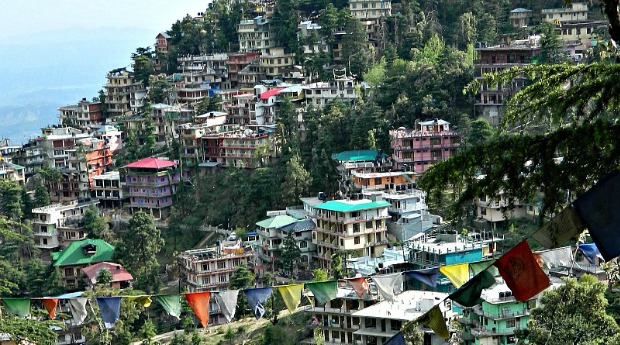

In northern India, nestled in the Himalayas, the town Upper Dharamasala provides a safe haven for a bustling Tibetan community. In 2012, a short stay introduced me to this beautiful town where, even in April, snow-capped mountains created a picturesque backdrop. Tibetan prayer flags fluttered over the paths and in the alpine forests. Bald monks in maroon robes strolled the streets, plucking at prayer beads. Upper Dharamasala (also known as Mcleod Ganj) looks more like a little Tibet rather than India and for good reason: It’s home not only to families of Tibetan refugee’s but also to the exiled Dalai Lama. They’re living across the mountains from their home, but they are safe.

In 1950, China invaded Tibet. The occupation has resulted in the deaths of hundreds of thousands of Tibetans, the imprisonment and torture of thousands more, and the displacement of tens of thousands. An uprising against Chinese rule failed in 1959 and Tibet’s political and spiritual leader the Dalai Lama was forced to flee to India for safety. The onset of the Cultural Revolution in 1966 caused Tibet’s religion to come under attack, destroying temples and forcing monks from their monasteries. While living conditions have improved since the early days of the occupation, Tibetans are still oppressed by the Chinese government, who refuse to acknowledge Tibet’s sovereignty.

Tibet’s occupation and the struggle of the Tibetans are ongoing but generally ignored by media outlets and in broader international political discussion. Because of this media blackout, Tibet’s plight is virtually unknown to the younger generation of the western world who did not have news exposure from when the occupation originally unfolded.

It was here in Upper Dharamasala that my travel buddies and I met Tenzin. Tenzin gladly told us of his experiences as a political refugee: a man who fled Tibet as a child and ended up in India.

Not minding our ignorance, he discussed his religion and experiences, telling us of how he came to India as a young boy. He was not shocked about our lack of knowledge of the Chinese occupation of Tibet and willingly chatted to us in the hope we would share his story to others who do not know of the troubles of the Tibetan people.

Over the past two years, Tenzin and I have kept in contact via Facebook, through which Tenzin has shared with me his story as a Tibetan refugee in India.

Tenzin travelled to India in 1997 without his family. He was only eight years old. The treacherous journey took over a month. They left Lhasa, the capital of Tibet, at midnight, having gathered in a deserted part of the city. Travelling with Tenzin were forty seven Tibetan strangers. Some were children, some were elderly, but the majority of them were between the ages of sixteen and twenty five.

A luggage truck arrived: their transport for the next six days. The truck driver gave the scared huddle of refugees some stern advice. Don’t make any noise. Don’t get out of the truck until you’re in a safe place.

For the next six days, Tenzin and his fellow Tibetans travelled in silence. It was a highly uncomfortable trip; everyone succumbed to travel sickness, plagued by pounding headaches and vomiting. The roads were rough and the truck shook all the occupants around. As Tenzin said, “Anyway, six days passed this way.”

On the sixth day, they needed to leave the moderate safety of the truck to bypass security check points. The driver tried to find a way around the checkpoints, but was unsuccessful and had to turn back and return to Lhasa, leaving his passengers to fend for themselves. From here on, the refugees were on foot; facing the Himalayan mountain range, home of the highest mountains in the world. It was the safest route out of Tibet- safest as it was the route least likely to meet Chinese border guards, but dangerous as they faced exhaustion, frost bite, exposure, starvation and dehydration.

The first challenge they faced was three fast flowing rivers. The first two were crossed quickly, helped immensely by two tall brothers who carried the luggage through the currents. Some bags split, the items lost in the swirling waters, but the boys were not discouraged. It took all night, but eventually they crossed the first two rivers. The third river was swollen from the melted snow off the mountains. A monk named Gyaltsen went first, balancing two children on his shoulders and some luggage on his back. Gyaltsen was by far the strongest swimmer and although the others tried, traipsing the river bank to find a narrower point, they couldn’t cross that night. The river swell died down after a day, and eventually everyone made it through the freezing waters of the river.

To avoid detection, the refugees slept during the day and walked at night. It was continuous hard work, walking through the mountains at night and several of the older refugees made the decision to turn back.

Tenzin, only a child, was severely exhausted and fatigued, too weak to even carry an empty bag while walking. Thistles stuck to their clothes, scratching them through the material. They had to stop regularly to pull them off.

Around the twenty five day mark, there was a food and water shortage. Things were looking dire for all the refugees. They had money, but being in such remote countryside, there was nowhere to buy supplies. Between the refugees and Nepal were around seven huge mountain ranges. It took days to cross them, walking through the thick ice and snow. The blinding white of the snow burned their eyes. One of the older men got severe frost bite on his leg and he ended up losing his leg. A child also got frost bite in his fingers, which also had to be amputated.

Finally they made it across the mountains and into Nepal, where they were quickly caught by the Nepalese police. They spent some time in Nepalese jail. There is a large community of Tibetan refugees living in Nepal due to Nepal’s laissez-faire approach to border control;

however laws began to tighten during the eighties. By the time Tenzin and his fellow Tibetans reached Nepal in 1997, Nepal had developed a new informal “Gentleman’s Agreement,” allowing refugees detained in Nepalese borders to be transferred to India safely. Tenzin and his friends were collected by the Tibetan Reception Centre and taken to India.

By this stage, all Tenzin had left in his possession were a few Yuan and a bag. When he left, he had biscuits and drinks, but he made the journey from Nepal to India without a single meal. Even now, he reminisces of the people who helped him and expresses how grateful he still is for their help.

In Dharamasala, Tenzin was sent to a Tibetan Children Village School. Before India, Tenzin had never been to school. Now, seventeen years later, Tenzin is settled in Bangalore, where he works as a chef in his own restaurant. India has provided Tenzin with the opportunities that Tibet couldn’t. He still travels regularly back to Dharamasala in northern India for religious teachings from the Dalai Lama. He practices Buddhism and still thinks fondly of Tibet, with the self-professed “innocent memories of childhood.”

Tenzin generously shares his knowledge of his home country and his dangerous journey to India, with the hope that the world can learn about the plight of the Tibetan people, both in Tibet and those exiled.

Australia’s news is perpetually flooded with stories of refugees travelling to Australia via boat. Fear of persecution causes many people to flee from their home countries, hoping to be protected by the international laws that protect people seeking asylum. The UN Refugee Convention recognises that refugees have a lawful right to enter a country to seek asylum. Despite Australia being a signatory to this convention, federal policies are attempting to resettle refugees in Cambodia and to turn back boats heading to Australia from Indonesia, rather than have more refugees enter our already overloaded system.

Policy and politicians are the centre of attention, while rarely do we hear the tales of desperation that led these people to take such dangerous journeys. No mother could imagine sending their eight year old child to cross the Himalayas or board a rickety boat to sail the Pacific Ocean unless they truly believed that it would lead them to a better life. Policies are too often driven by politicians with agendas rather than by compassion or consideration for our fellow humans.

“Love and compassion are necessities, not luxuries. Without them humanity cannot survive”-The Dalai Lama.

I met a Tibetan young man in his 20s running a small cafe in Mcleodganj. He shared his story of how he crossed over from Lhasa into Nepal and finally to India. That made me Google on the subjected, chanced to land up here.

It’s a plight to see the struggles Tibetans are going through. Hoping international media to pick up this issue seriously.

Loved reading your article.